3: Towards zero shot

Conventional dialog understanding is based on intent classification, which requires labeling a new dataset and training a separate model for each new intent. This process is not only time-consuming but also expensive, and may be a primary obstacle to chatbot development.

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT have gained widespread attention due to their remarkable ability to perform multiple tasks with impressive accuracy without requiring any specialized training. This is great new for chatbot development. But how did these models acquire their magical zero-shot learning capability? It is essential for chatbot developers to have a conceptual-level understanding of this technology in order to utilize LLMs more effectively, particularly since language understanding is a crucial component of chatbots. However, what exactly is machine learning?

Machine Learning Basics

To enable a computer to perform a task, we usually need to create a function by declaring and implementing it. Declaration involves defining the function’s name, return type, and parameter types. Implementation entails hard-coding a step-by-step procedure that the computer can follow to provide the correct result for given input parameters. It is possible to have multiple implementations for the same function declaration.

However, many real world tasks are extremely difficult or even impossible to program via imperative hard-coding. For instance, determining whether an input image contains a car or not can be a challenging task, and basically intractable to the imperative approach. We need an alternative to hard-coding to implement such functions, that is where machine learning comes into play.

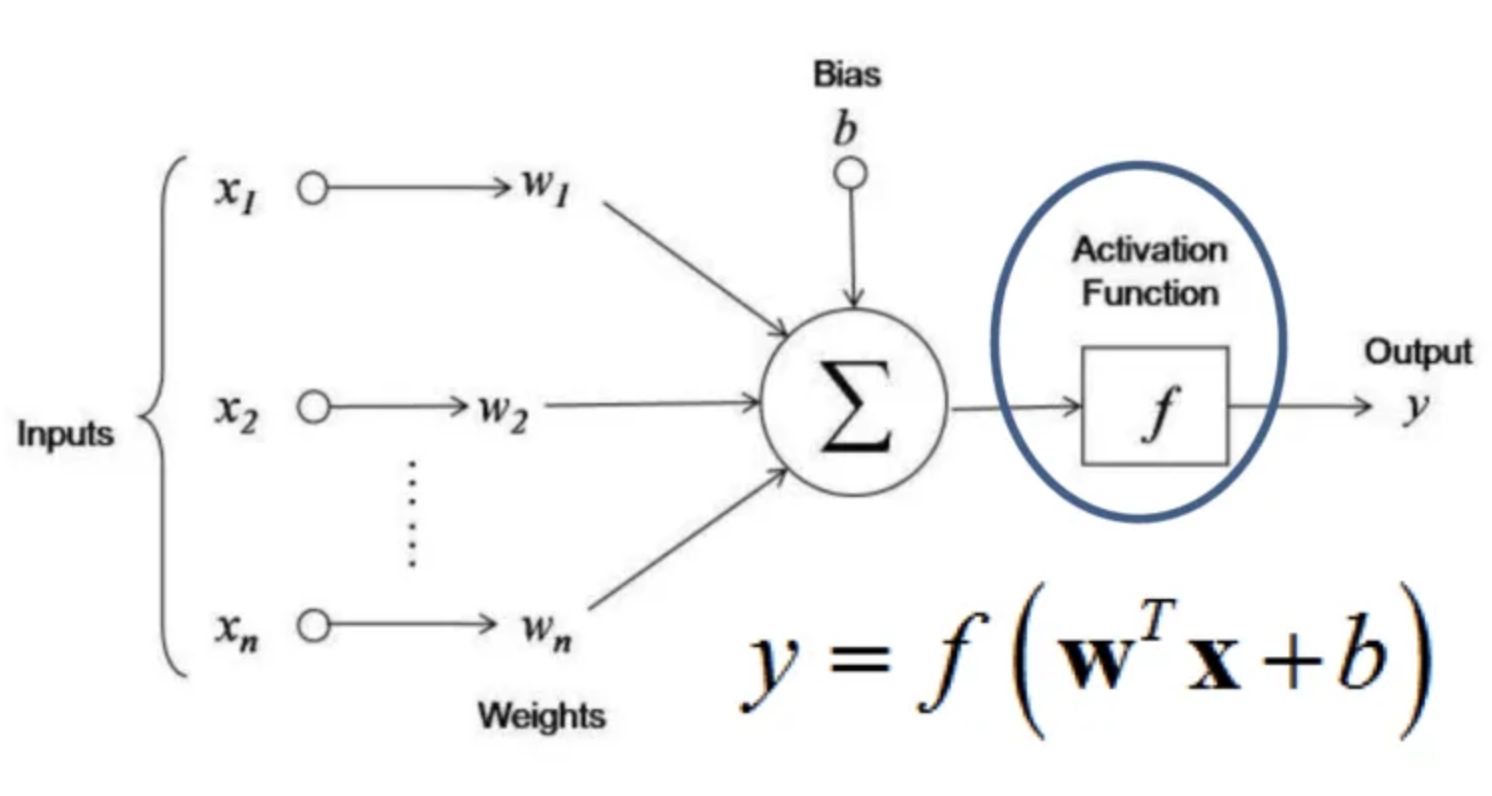

Given a target function declaration, machine learning can create a function implementation in form of machine learning model. Machine learning model is a extension function to the target function, which means it has all the parameters from the target functions, and some model parameters. Model parameters (w) can bind to inputs (x), or some internal factors like bias (b) in the simple neural network model from above. The machine learning model can be used as target function implementation simply by fixing the model parameter with some values, typically based on training.

Given a target function declaration, machine learning can create a function implementation in the form of a machine learning model. The machine learning model is an extension of the target function, which means it has all the parameters from the target function, as well as some model parameters (w). These model parameters can be bound to inputs (x), for example using dot product <(w, b), (x, 1)> in a simple neural network model. The machine learning model can be used as the target function implementation simply by fixing the model parameters (w) with some values, typically based on training.

Training a model is machine learning way to implement a function. For example, given a dataset of example images, each labeled with a “yes” or “no” indicating whether it contains a car, training determines values for model parameters (w). Typically the values (known as weights) for model parameter is set to the ones that can map image to prediction of “yes” or “no” with highest accuracy, or simply agree with true label most.

Some special considerations:

Multitask models

Often, we need to perform multiple tasks on the same input, and it is beneficial for models to share some common parameters. One approach is to train these models using a multi-stage process. In the initial stages, the focus is on training a base or foundation model that models the input data into an intermediate representation in a task-independent manner. In the later stages, the focus is on training the task-specific model that maps from this shared, task-independent representation of the input data to the task-dependent output. The performance of the final model depends heavily on both the foundation model and the learning algorithm used in the later stages. A stronger foundation model generally requires fewer shots.

Generative and discriminative

From a statistical perspective, there are two types of models: generative and discriminant. A generative model estimates the probability distribution of the data itself P(input), while a discriminant model estimates the conditional probability of the output given the input P(output|input).

Models can also be decomposed, with a generative model potentially being broken down into discriminative component models. For instance, while language models are generative on a sequence of tokens, they are typically decomposed into discriminative models that estimate the conditional probability of each token given the history of the sequence up to that point. In other words, the likelihood of the entire sequence is calculated as the product of the conditional probability of each token given its position in the sequence, from beginning to end.

Modern models like LLMs, including GPT, have billions of model parameters and are much more complex in structure. Despite their complexity, these models can still be understood conceptually using the approach described earlier. With this conceptual model, three simple tricks are responsible for the magic of zero-shot learning.

Trick #1: Solve a problem by modeling its output as input

A discriminant function f(x) -> y that maps input to output can be easily implemented by its generative extension (by extension, we simply mean function with more parameters) that contains the output of the target function as the addition input parameter: likelihood(x, y; w). During training, we can find the model parameter that maximizes likelihood of both the input and output, and then during inference time, we find the output that produces the highest likelihood for given input.

As an example, say that we need to determine whether user want to buy a ticket based on his input utterance “I need to fly to Beijing tomorrow”. The discriminant solution is to evaluate P(buy_ticket|utterance) directly. Given a well trained generative model in form of P(utterance, action_mentioned), we can simply compare these two values:

likelihood(“I need to fly to Beijing tomorrow”, “buy airline ticket”)

likelihood(“I need to fly to Beijing tomorrow”, “not buy airline ticket”)

hopefully the first likelihood is evaluated to be larger thus we can conclude user does want to buy ticket.

Using this simple trick, we can suddenly use one model to make predictions for any intent. However, if we have not provided any examples for a particular intent during training, how can we expect the model to make reasonable predictions? This is where the second trick comes into play.

Trick #2: Just Embed that

To find the model parameters that best explain the training data, all practical learning algorithms rely on numerical optimization. Because of this, we need to encode the words, commonly known as tokens into numerical vectors that can be used as input to machine learning model.

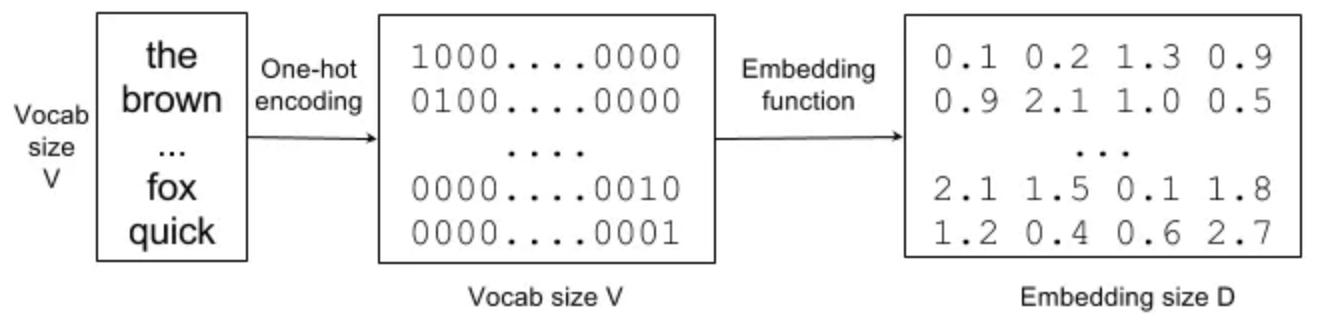

For quite a while, the text encoding of choice has been one-hot encoding. It represents a token as a binary vector, where each dimension of the vector corresponds to a unique token. If we have a vocabulary of V tokens, the binary vector we produce for any token should have a dimension of V. For the above example, the word “the” could be represented by a one-hot vector with a value of 1 in the first position and 0s in all other positions.

One-hot encoding of a token does not capture the relationships between tokens. For example, if we’re learning a model for the skill “buy ticket,” we know nothing about the skill “purchase airfare.” To address this issue, people started using embeddings. The idea is simple: instead of using a sparse one-hot vector to represent a token, we use a dense vector instead, and hope that the embeddings for these two phrases will be similar in dot product sense. Unfortunately, it’s not clear how to get such embeddings, and there are no known analytical solutions to compute them. So we have to train them using data, and for that, we need one last trick.

Trick #3: Self-learning, on Web Crawl with Transformer

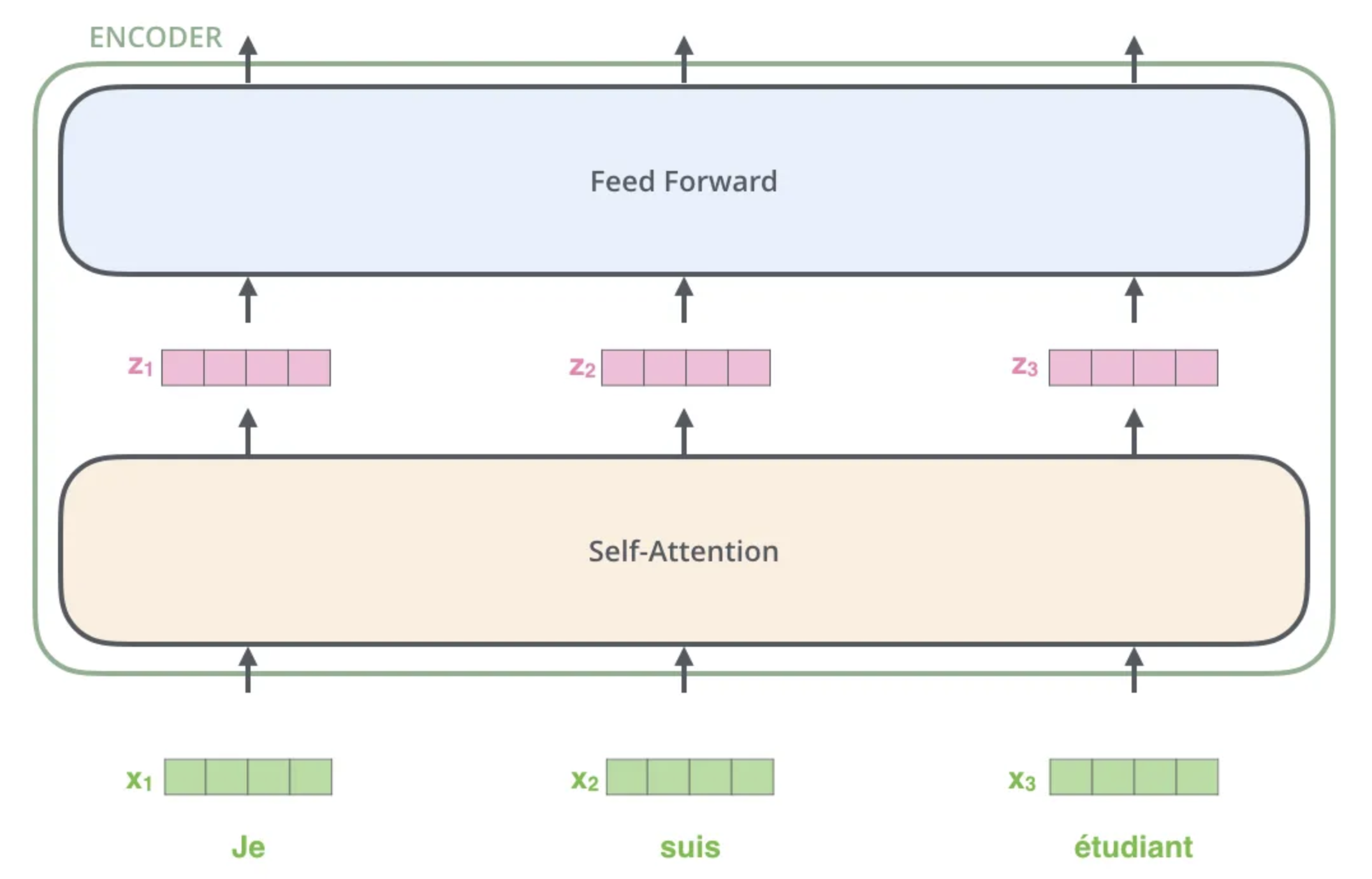

Since the same phrases can have different meanings in different contexts, and different phrases can mean the same thing, we need an effective model to compute representations for sequences of tokens in a context dependent fashion. The transformer architecture, developed by a team of researchers at Google, has proven to be a capable choice.

As we’ve shifted more aspects of our lives online, we’ve amassed an enormous corpus of natural language documents that are freely available in every subject and language. This presents a prime opportunity for self-learning or self-supervised learning to take place.

Rather than relying on explicit human labeling or annotation, self learning creates a high-quality dataset by masking or corrupting parts of the data and use the missing or corrupted parts as label. For example, from “I want to buy a ticket to Beijing”, we can create many labeled pairs, such as (“I want to buy a [mask] to Beijing”, “ticket”), or ( “I want to buy a ticket to”, “Beijing”), etc.

By embedding each token and computing the representation for sequence based on these embedding, a large enough transformer model, trained with a large dump of web crawl via masking, next token prediction and other form of self learning, will have a good “understanding” on both the token, and its context for any sentence. Since the similar words or phrases will occur in the similar context, so it is likely that they have similar embedding as well as representation, which is also generally the case after these self-learning.

A task model based on such foundation model can thus make quality predictions on any targets even when these targets are NOT observed during later stage training. In fact, by further embedding the task into the generative model, model like InstructGPT can even perform well on the tasks that it is not trained on.

Parting words

Instead of learning each task from scratch, we can invest in pretraining a large foundation model through self-supervised learning on a massive corpus of natural language documents. By fine-tuning this model with as many tasks as possible, we can create a foundation that easily adapts to different tasks without any additional labeling effort.

Chatbot platforms, such as OpenCUI, built on this paradigm allow developers to focus only on interaction logic without worrying about dialogue understanding. This greatly reduces the cost of chatbot development, thus democratizing conversational experiences.